Out With Aliens, In With Alienation

On the science-free sci-fi of J.G. Ballard's Concrete Island

Even when J.G. Ballard was writing his earliest novels—which, though more concerned with climate collapse than interplanetary travel, were at least plausibly recognizable as science fiction—he was up to something unusual for the genre with which he claimed affiliation. This was perhaps a fitting strangeness for a Brit who grew up in the colonial wonderland of the Shanghai International Settlement, who as a tween was interned by the Japanese for the final two years of World War II, and who then came of age grappling with the byzantine social customs of British secondary school. In fact, he was entirely unacquainted with sci-fi until age 23, when he made first contact in a bus depot magazine rack while stationed in Saskatchewan with the Royal Air Force.

Taken with these stories’ “huge vitality,” he quickly determined he could use their tools to “translate the visually surreal into prose”—an approach he had been circling in his early forays into fiction. Yet he found the genre wanting almost immediately, calling it “‘ripe for change, if not outright takeover.” He “wanted to subvert everything…to kill outer space stone dead…to kill the far future and focus on inner space and the next five minutes.” Ultimately, the goal was to abandon sci-fi’s “explicit social and moral preoccupations” in favor of “ontological objectives – the understanding of time, landscape and identity.” One of his earliest published stories was accompanied by a note on the Surrealists, “whose dreamscapes, manic fantasies and feedback from the Id are as near to the future, and the present, as any intrepid spaceman rocketing around the galactic centrifuge.”

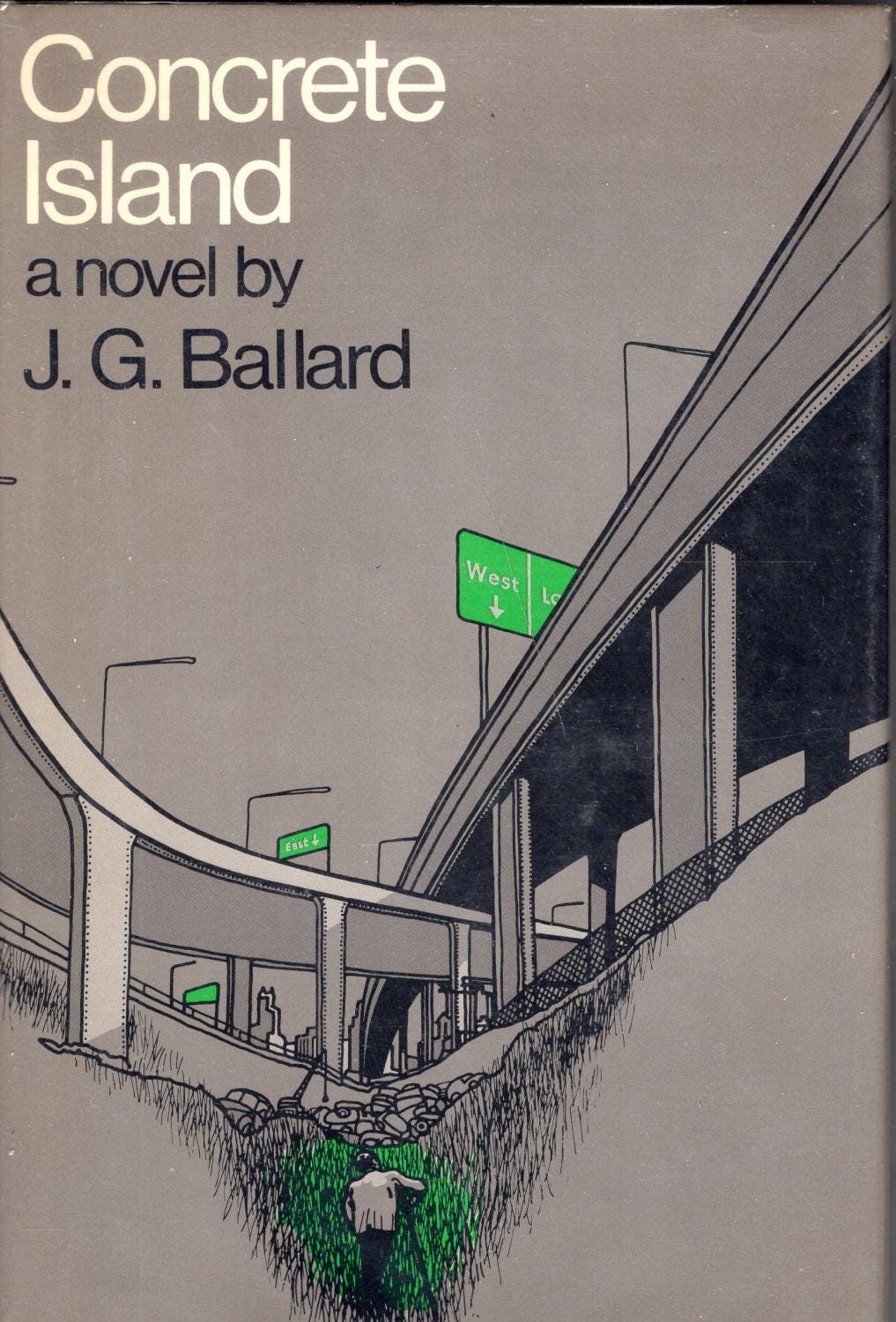

By the 1970s, his plots—to the extent that his novels grew that kind of greenery at all—had moved even further from conventionally recognizable sci-fi. Still, for much of the decade, he persisted in labeling his work as such, a move he later came to regret. The fiction of Concrete Island (1974), published during this period, lacks anything remotely sciencey. There’s no robots, time traveling, or UFOs. And yet there’s something about it that tastes of science fiction; in its dystopian extremity, it’s written with the genre’s grammar, if not its words. But, instead of extrapolating its extremes outward to the future, it burrows deeper into the strangeness of the present than any realism ever would.

The novel concerns an affluent desk-jockey who crashes his car onto a deceptively large traffic island surrounded by highway interchanges. He’s injured, but soon realizes that a bigger impediment to his rescue is that the enveloping traffic won’t stop for him. This is a shipwreck tale set in the belly of the metropole instead of a Caribbean island. And as with overseas colonies, the traffic island sits uneasily in the interstices of (post-?) modernity—serving an essential purpose for the dominant society, but largely hidden from view. This situation is near-farcical—Maitland, our Crusoe, can literally see his own office tower from where he’s marooned—but something sadder and stranger is going on.

The crash, “like a vent of hell,” just sort of happens to Maitland. And yet “he had almost willfully devised” it, perhaps to escape the alienation of his marriage, his situationship with the mistress, his office job, and comfortably bland life. This would all be a bit easier to stomach if he could just further transactionalize it all, and pay “hard cash across the high-priced counters of these relationships.” In his more feverish moments, he identifies with the island itself, and the estranged space only further isolates him from society: “a thin but distinct mental screen divided him from the traffic moving past.” Society, however, is inescapable, as evidenced by the median’s two other inhabitants, who Maitland eventually discovers. Like the island itself, they occupy a kind of shadow modernity left behind by the surrounding rush for progress and profit.

The island is a palimpsest of London, “a wound that never healed.” In its past lives, it was an air raid shelter, a movie theater, a cemeterial churchyard. None of these former uses have been fully buried (or, maybe, properly reckoned with), and their evidence haunts the island alongside the burned out chassis from myriad other car crashes, a mentally-disabled former trapeze artist, and a young sex worker who seems to be on the run from institutionalization or abuse.

But Maitland’s time with people and things his society has found it convenient to forget—and his growing tenure as a castaway himself—fails to get his mind right. Instead, he seeks to reconstruct the hierarchies he’d quietly benefited from all his life. He is both irritated by the girl’s provocative sexuality and attracted to it. Eventually he exploits it himself. He pisses on the face of the former circus performer to assert his dominance, rides him around as a “beast of burden,” and beats him with a crutch. He begins to enjoy humiliating and manipulating his new neighbors. “I’ve changed the whole economy of your life,” he lords over the man. “Don’t forget that.”

So much for a renunciation of sci-fi’s “ social and moral preoccupations.” But perhaps with Concrete Island, Ballard was up to something similar as with Crash, which he once called “not a cautionary tale,” but “a psychopathic hymn which has a point.” So out with the futuristic didacticism of so much science fiction, and in with critique through the surrealizing of “everyday life” and “the external world which is now…the paramount realm of fantasy.” And though they’re inextricable from the book’s social critique, it’s this—the peculiar, elegiac language he uses to defamiliarize our built environment—that’s Concrete Island’s most original aspect, and the hardest to shake.

A brand new overpass’s “white concrete crossed the sky like the wall of some immense aerial palace” with a labyrinth of ascent ramps and feeder lanes,” causing Maitland to feel “himself alone on an alien planet abandoned by its inhabitants, a race of motorway builders who had long since vanished but had bequeathed to him this concrete wilderness.” Our psychopath begins to hear the hymn, listening to the speeding highway congestion with “his eye on the red disc of the sun sinking behind the apartment blocks. The glass curtain-walling was jewelled by the light. The roar of the traffic seemed to come from the sun.” Eventually a new perspective on the relationship of place and time emerges. Ballard sings: “the roofs of the air-raid shelters rose around them like the backs of ancient animals buried asleep in the soil.” The melody of his prose tells us that they won’t sleep forever. But until then, now is the weird, weird time of monsters.