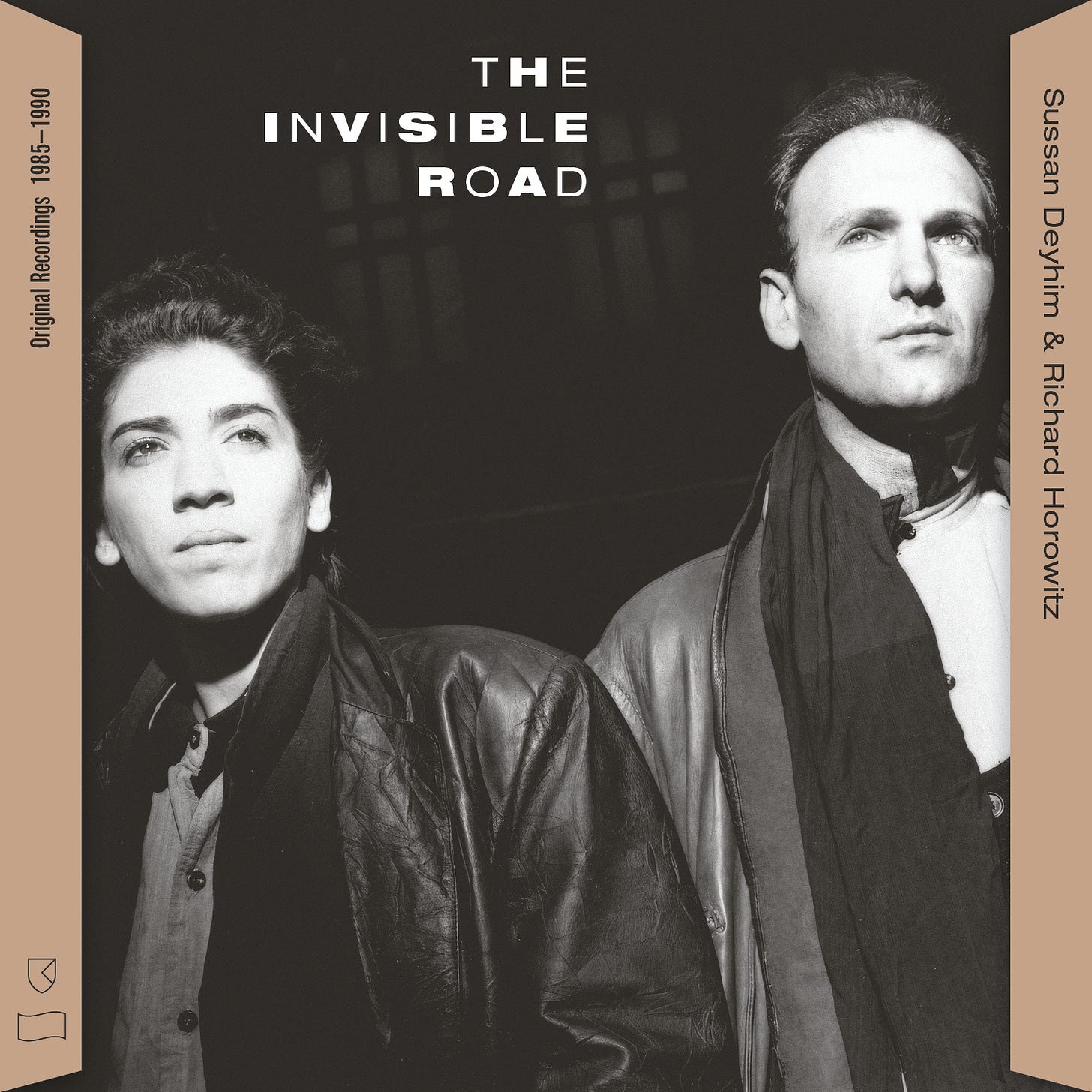

I wrote the liner notes for Sussan Deyhim & Richard Horowitz’s The Invisible Road: Original Recordings, 1985–1990, an album of unreleased recordings by two Downtown weirdos who refused to be slotted into preassigned categories, musical or otherwise. It’s out now on RVNG Intl. / Freedom to Spend.

Richard passed away while I was working on the liner notes, so it was an additional privilege and challenge to try to honor his memory, as well as Sussan’s living legacy. If you live in New York, you can also see Sussan do both live at Roulette on Tuesday.

The full liner notes are only available with the vinyl edition, but I got permission to share a few excerpts below. Maybe this week especially, you could use their rejection of the path prescribed, and vision of other ways forward.

Hear the sound. More a limbo than a song. Navai, in Persian—a calling. Time suspended, tension unresolved. A River Styx dog-paddled by a multi-headed hydra of voices. Spirits from below and beyond speak and beckon. All history present in that sound.

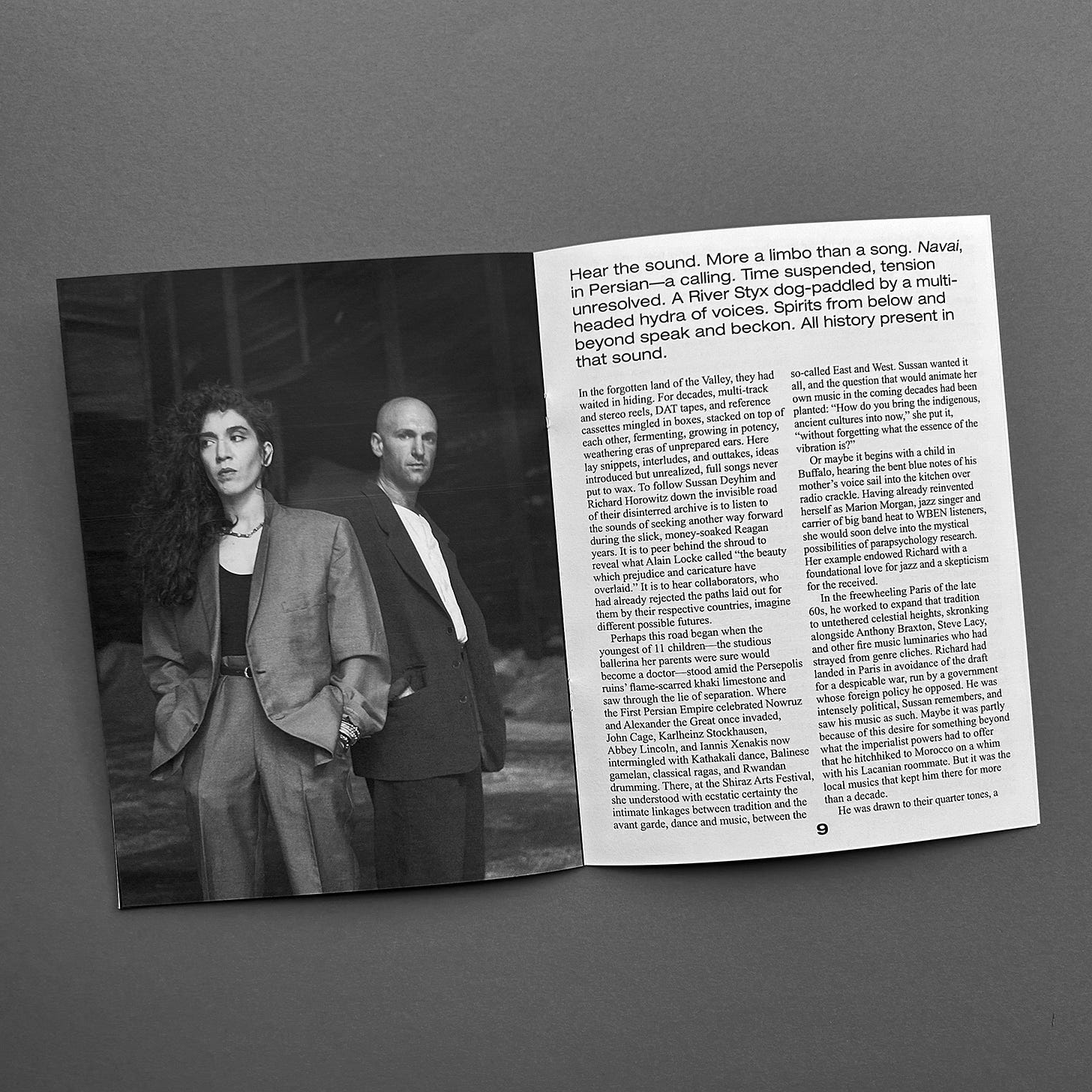

In the forgotten land of the Valley, they had waited in hiding. For decades, multi-track and stereo reels, DAT tapes, and reference cassettes mingled in boxes, stacked on top of each other, fermenting, growing in potency, weathering eras of unprepared ears. Here lay snippets, interludes, and outtakes, ideas introduced but unrealized, full songs never put to wax. To follow Sussan Deyhim and Richard Horowitz down the invisible road of their disinterred archive is to listen to the sounds of seeking another way forward during the slick, money-soaked Reagan years. It is to peer behind the shroud to reveal what Alain Locke called “the beauty which prejudice and caricature have overlaid.” It is to hear collaborators, who had already rejected the paths laid out for them by their respective countries, imagine different possible futures.

……..

Though she would grow frustrated with the “golden cage” of the ballet tradition, she continued to carry the spirit of dance with her. As a ballerina, she had become attuned to the ancient technology of the body and the somatic intuition of vocal techniques. “You don’t see your vocal cords,” she says, “and have no access to the internals of your body.” This intimate understanding of the physicality behind creative expression helped her appreciate the “different musculature” required to jump between singing styles. These pivots could easily shred a voice not in tune with its apparatus.

In the 80’s, “world music,” Robert Christgau once wrote, “was a concept whose geoeconomic time had come.” The breakneck pace of international trade was flattening the globe, and the music industry began to see Americans and Europeans as open to some sounds from freshly decolonized places. As the business optimized its marketing of recordings from around the world, it trafficked in stereotypes and limited ideas of what non-Western artists could do. “They had a rigid idea about what authenticity meant for an artist like me,” Sussan says. “My own thought process just didn't exist in the vocabulary of their understanding.” Richard and Sussan’s experiments—along with the creations of some of their Downtown collaborators, like Bill Laswell—were a bulwark against that commercial speciousness; steeped in tradition, they are unsettled and open, and suspicious of being pigeonholed or pinned down.

This freedom is jazz’s fundamental spirit , transmuted into something strange and different, like Jon Hassell's trumpet sound passing through uncanny patches. The genre’s core principle of mutual improvisation would also become central to Sussan and Richard’s composition process. Sometimes she would start out loud with a vocal idea, and he would compose around it, both of them extrapolating from there. Or Richard might lay down gestural production, and she’d overdub herself finding harmonized avenues into his cloudy sonic structures, until all eight tracks of the tape were brimming with them exploring together.

They sought to make music that was, in Sussan’s words, “free of any specific cultural reference.” Perhaps an impossible task—but one attempted by uniting elements from innumerable traditions into a sound entirely their own. You’d probably want to find a new cultural context too, if the one that raised you was frothing for gruesome war or newly hostile to creative expression and people like you.

……..

A group of psychics, friends of Richard’s mother, once heard his ney’s oneiric warble and implored him to use his playing to help people transition from life to death. Though he never took them up on their suggestion in the literal sense, the ruminant and cerebral music he made with Sussan is well-suited for other kinds of transitions. Maybe the change is simply one of affective states—or perhaps something more sweeping. The music here lives in that ambiguous zone of the interlude—unbeholden, curious, open to interpretation. It is still, after decades in boxes, unfolding and figuring itself out. In its refusal to settle on a clear answer, the beautiful questions it raises up off in the distance give us a glimpse of an ecstatic spiritual vision. The world still hasn’t caught up.